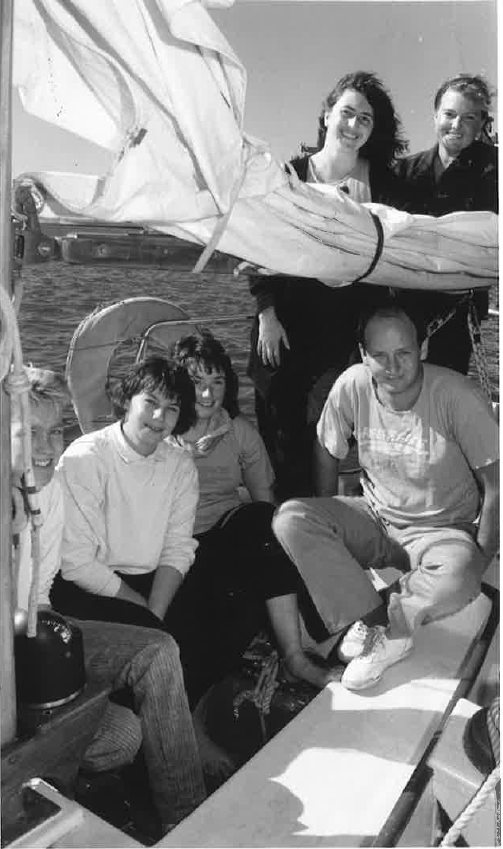

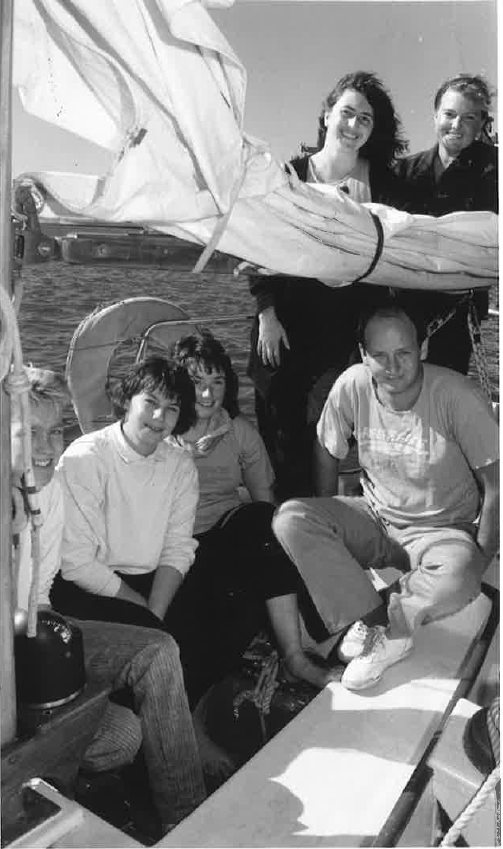

Sandy Scheltema was a member of the crew of the Greenpeace yacht Vega when it set off on 15 April 1987 from Sydney, Australia on a cruise to oppose nuclear activities at sea. Sandy is opposed to nuclear weapons and also likes to sail. This made her jump at the opportunity to sail with the Vega.

Less than two months later, it was all over. When the Vega reached Brisbane, capital of the state of Queensland, it was rammed by a police boat and impounded indefinitely. Seven Greenpeace members and crew of the Vega were arrested and face up to seven years gaol for blocking a waterway. Two were injured.

Sandy, by chance, was off the Vega at the time and was not one of those arrested. After these events, she worked full-time in support of Greenpeace and those arrested, writing letters, organising publicity and giving numerous talks. It wasn't sailing, but it was important.

The Vega set off from Sydney as part of Greenpeace's worldwide Campaign for Nuclear Free Seas. Its aim was to publicise the Greenpeace campaign through its visits along the eastern Australian coastline. These plans were disrupted by the Queensland police.

For several years, ships and submarines from the United States Navy have been making regular visits to Australian ports. Many of these vessels are nuclear-powered, and many also certainly carry nuclear weapons. These visits by nuclear ships have become a major focus for protest by the Australian peace movement. 'Peace squadrons' have been formed in several port cities. They comprise all sorts of water craft, and these squadrons have 'greeted' many of the US ships.

Activists in these peace squadrons are committed to nonviolence, and plan and train for their activities to avoid any danger to sailors or bystanders. Some of the activists themselves have taken serious risks by getting in the way of the US ships, all in an attempt to slow them down and disrupt 'nuclear business as usual'.

In most cases the protesters liaise with police concerning their actions.

It so happened that when the Vega reached Brisbane, the local peace squadron, the 'Peace and Environment Fleet', was getting ready to protest the visit of the nuclear-armed frigate USS Ramsey. It was only natural that the Vega join this action.

On 9 June 1987, the Vega was moored in the ship channel of the Brisbane River when the Ramsey began its entry into the river. There was plenty of time for the Ramsey to alter its course, remain in the ship channel and yet avoid the Vega. The Ramsey knew of the position of the Vega, both visually and through radio communication from the Greenpeace vessel.

As mentioned, the Vega was only one of many craft being positioned to block the Ramsey. Indeed, only four of the Vega crew were on board. Three others were in a rubber dinghy called a zodiac, and Sandy was in another zodiac where she was able to take a number of photographs.

Queensland police were also active on the water, protecting the Ramsey from harassment. As the Ramsey approached the Vega at about 10.30am, a police launch, seeing the threat to the Vega - or from the Vega - rammed it to get it out of the way of the Ramsey. Seven members of the crew of the Vega were arrested, and the yacht itself was impounded.

Those arrested included the British captain Chris Bone, five Australians and one New Zealander.

Queensland water police sit on skipper Chris Bone's chest during protest on the Brisbane River over the arrival of the US frigate USS Ramsey, 9 June 1987. Photo: Sandy Scheltema/Greenpeace.

This was the first time that a Greenpeace vessel had been impounded in Australia. Even more upsetting were the severe criminal charges brought against those arrested. They were charged with obstructing a waterway, an offence which can result in up to seven years imprisonment with hard labour.

The style of the arrests was worrying. One member after another was arrested, questioned and charged with offences. Furthermore, the offences gradually increased in number. The crew in the dinghy were also charged with assaulting the police and obstructing the police in the course of their duties.

The increase in the charges have made the defendants apprehensive even about going out in public alone, since they think they might be arrested for a trivial or non-existent offence. They stay together to provide each other with witnesses.

Sandy was not arrested, but the arrests shaped her life too. Instead of proceeding with the cruise of the Vega, she spent months helping organise opposition to the charges against the Greenpeace members.

The impounding of the Vega is symbolic of a continuing confrontation between citizens' action and the repressive use of police power in the state of Queensland. To fully understand the Vega case, some background is necessary.

Located on the Australian continent are a large number of United States military and intelligence facilities. The three most important are commonly known as Pine Gap, Nurrungar and North West Cape. Pine Gap and Nurrungar, both located in central Australia, are communications links for satellite early warning systems; they also collect electronic intelligence. North West Cape, on the west coast of Australia, is a major station for submarine communication by very low frequency radiation.

These particular bases began operation in the period 1968-1971. There are numerous other US military and intelligence facilities in Australia as well. Although officially dubbed 'joint facilities' of the US and Australian governments, in practice they are run by the Americans. For many years their true functions have been hidden from the Australian public by successive Australian governments, although much of the information was openly available in the US and exposed by Australian researchers, especially Desmond Ball.

In the past few years there has been a bit more official information about the role of the bases. The government now says that they protect nuclear deterrence by monitoring arms control agreements, and hence are entirely beneficial. Yet available evidence suggests that such monitoring is a minor function of the bases and that they spend much more time supporting US war-fighting capabilities. It is widely accepted that Pine Gap, North West Cape and Nurrungar are the three most likely nuclear targets in Australia.

The Australian peace movement has for many years, as a key part of its activities, opposed the US bases. Concerted efforts have been made to get the Australian Labor Party to oppose the bases; these efforts have consistently failed to affect Labor government policy. There have also been major direct actions against the bases, in spite of their remote location. Most notable was the Women's Peace Camp at Pine Gap in 1983.

The integration of Australia into US military planning was furthered in the early 1980s with the introduction of regular visits by nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed ships to Australian ports, and also visits by US B-52 bombers to an air base near Darwin. This was a major step in the penetration of US military operations into Australia. At the time, the Australian peace movement was just beginning to expand and its relatively weak protests were ignored.

The peace movement's focus on US bases and ship visits makes it seem, in the eyes of some critics, to be anti-American. There are no Soviet or other foreign military bases or nuclear ship visits to oppose.

Australia's nuclear connections provide a major contrast with New Zealand, which in other ways is quite similar to Australia. New Zealand has never hosted a major US strategic intelligence base, and in 1984 the newly elected Labour government banned visits by nuclear-armed or nuclear-powered vessels, causing a rift in the military alliance with the United States. The difference is that Australia became hooked into US global nuclear plans at an early stage, cementing relations between the two countries' military, intelligence and foreign policy apparatuses and establishing the connection as 'natural' in the minds of many Australians. In New Zealand, without these connections, the peace movement and its allies were able to thwart US initiatives and to capture mainstream support.

The US Navy will neither confirm nor deny the presence of nuclear weapons on its ships. Informed observers say that many vessels visiting Australian ports do carry nuclear weapons. The introduction of US ship visits has now made Australian ports much more likely to be nuclear targets.

Most of the Australian ports visited by US ships are near to major population centres. This means that it is much easier to organise protests at these visits than at the remote US military bases. Peace squadrons have been organised in several cities. These have provided the focus for much of the ongoing work in nonviolent action training in the Australian peace movement.

Greenpeace is an international - or perhaps better described as transnational - organisation which focusses on environmental issues. Its trademark is nonviolent action in the form of tightly organised direct intervention. For example, ships have been sailed into nuclear test areas, and activists have interrupted the slaughter of baby seals and the dumping of nuclear waste in the oceans. Greenpeace actions are often highly visible and widely publicised.

High-profile actions by Greenpeace are backed up by careful research, planning, training and much behind-the-scenes work. The effectiveness of some Greenpeace actions depends on secrecy and central planning. Some activists in other organisations, who favour consensus decision-making and egalitarian politics, at times criticise Greenpeace's insider and top-down methods. But Greenpeace is recognised by most as a model of effectiveness and commitment.

In July 1987, Greenpeace launched a new international campaign to promote 'Nuclear Free Seas'. July 1987 was the second anniversary of the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior in New Zealand by agents of the French secret service. This bombing, which sank the Rainbow Warrior and killed one crew member, immensely increased the visibility of Greenpeace around the world.

In Australia, Greenpeace's nuclear free seas campaign fitted neatly into already existing discussions in the peace movement to focus on 'sea links' between the Australian and US militaries. It just so happened that it was the Vega and hence Greenpeace which were singled out for attention by the Queensland police.

Police sit on the impounded Vega during the launching of the "Free Vega - Preserve the Pacific" campaign, 16 July 1987. Photo: Sandy Scheltema/Greenpeace.

Queensland, one of the six states in the Australian federal system of government, stands apart from the others in its government's intolerance of political dissent. Characterised as the 'deep north', in Queensland political freedoms are considered by the government to be privileges rather than rights. Although it is wrong to exaggerate the differences between Queensland and other states, political repression is an especially serious problem in Queensland.

The Australian constitution provides no formal right of free speech or free assembly. Generally these are considered to be traditional rights, as in Britain. In Queensland the government has attempted to erode these rights through legislation and police action. This has been opposed by various citizen groups.

Until 1957, the Australian Labor Party formed governments in Queensland. These Labor governments had a poor record on civil liberties. Since 1957 Queensland has been ruled by a coalition of the Liberal (conservative) and Country parties. The Country Party, now renamed the National Party, has prospered under a gerrymander which gives it many seats in parliament with a minimum of votes. In the past few years the National Party has been able to form a government without the support of the Liberals.

Attacks on civil liberties have usually occurred in response to challenges by social movements or trade unions. With the development in the late 1960s of opposition to Australian participation in the Vietnam war, the Queensland government invoked its existing regulations of the Traffic Act. Permits had to be obtained to hold meetings or processions and these could be denied with no reason given. Numerous arrests were made, especially in the capital Brisbane, and the anti-Vietnam protests became linked to protests to support civil liberties.

When the South African rugby union team, the Springboks, visited Australia in 1971, it was the focus for major demonstrations. When the Springboks toured Queensland, the government went to the length of declaring a state of emergency. It was common for police to assault protesters, and also to ignore spectator assaults on protesters.

In 1977, the Premier of Queensland, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, declared that political street marches were henceforth illegal. The right of appeal to a magistrate was removed, and Bjelke-Petersen said that all applications for permits would be turned down. This ban triggered the formation of the 'Right to March' movement, which for three years challenged the government. Supported by civil libertarians, the anti-uranium movement, the churches and some politicians, the right to march campaign generated considerable support.

The ban on political street marches seems initially to have helped the government to gain electoral support as a defender of 'law and order'. But the exposure of police brutality and harassment of protesters eventually caused many influential figures, including the executive of the Queensland National Party, to oppose the ban. Significantly, the Queensland Labor Party provided only lukewarm opposition to the ban, and the mass media in Queensland generally supported it.

There are many other examples of political attacks on dissent by the Queensland government. These include repressive treatment of Aborigines, para-military raids on 'hippies', attacks on abortion clinics, censorship of books and films, intervention in the education system, attacks on trade unions and interference in appointments and promotions in the government bureaucracy.

Recent Queensland drug legislation allows police to enter and search premises without a warrant, to conduct internal and body cavity searches, and to hold suspects 48 hours without making a charge. If specified illegal drugs are found on one's premises, a person can be charged with 'permitting the use of a place' and receive up to 15 years in prison with hard labour.

This legislation, called the 'Drugs Misuse Bill', appears open to serious misuse for political purposes by police. Many activists fear that they will be victimised, for example by police planting drugs on their property in the course of a search.

Attacks on civil liberties in Queensland have usually been in order to attack a particular social movement. In the 1960s, the attacks were against those opposing Australian involvement in the Vietnam war. The 1977 ban on marches was to a great extent designed to squash the anti-uranium movement and allow uranium export from Queensland's Mary Kathleen mine to continue. It is in this context that the impounding of the Vega and the severe charges against seven Greenpeace members must be seen.

Governments in many countries have periodically laid severe charges against dissenters in an attempt to break the back of social protest. This happened in Britain in the early 1960s to thwart increasingly militant peace activists. In the US, heavy sentences have been passed against nonviolent direct activists who have intervened at nuclear facilities.

The potential for seven-year prison sentences for the Greenpeace members may serve to intimidate future protesters against US nuclear ship visits. This is an obvious aim of the charges, considering that many peaceful protests have been held in Brisbane and elsewhere without any charges approaching this magnitude being laid against protesters.

Undoubtedly, the charges are intimidating. Greenpeace has been cautious about publicising the case because it is sub judice. Yet to avoid publicity is to play into the hands of the government by allowing active protest to be sidetracked into judicial proceedings.

In picking the Vega and Greenpeace for attack, the Queensland government has taken on a formidable opponent. Greenpeace is skilled in media work and has an international network. It can count on support from a wide range of individuals and organisations.

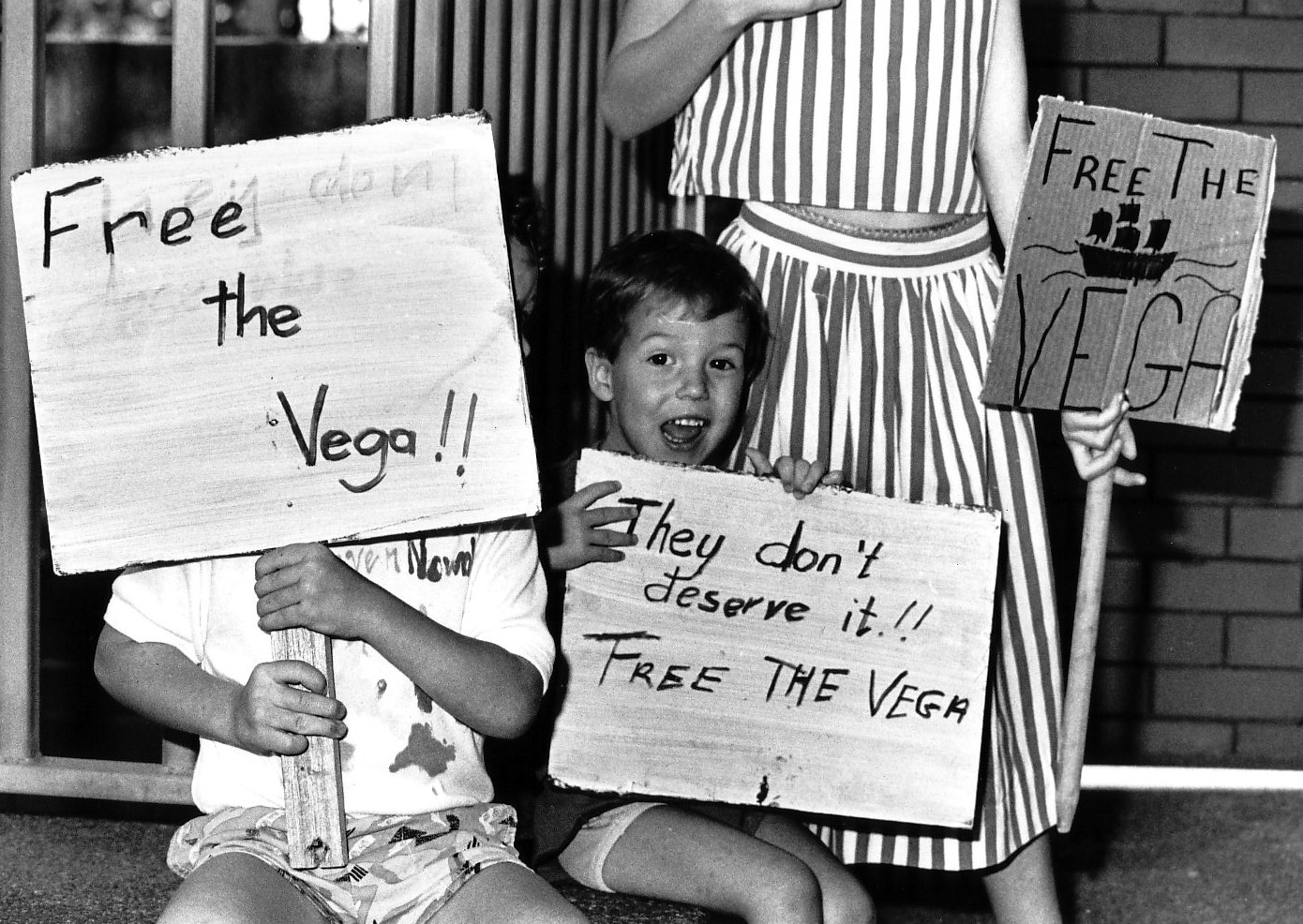

Children outside the court during committal proceedings, 23 September 1987. They made the signs themselves. About 50 people were present. Local press coverage was good. Photo: Sandy Scheltema/Greenpeace.

The Vega was released on 2 October, nearly four months after being impounded. During this time the police clearly had been afraid that Greenpeace would 'liberate' the vessel in a nonviolent raid. On release, both the mast and the propeller of the Vega were found to be chained.

One of the Brisbane Seven, Sarah Hancock, had also been charged with assaulting police. After some months the charges were dropped, apparently because there was convincing evidence that the police version of events could not be sustained.

Adding to the difficulties facing the prosecution, the Queensland government is now in disarray. The Fitzgerald Inquiry into police corruption is finding material uncomfortably close to leading figures in the government. The Police Commissioner has been 'stood aside'. On 1 December 1987, the long-serving and autocratic Premier of the state, Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen, resigned in the face of opposition from other members of his party.

Sandy Scheltema set out for a cruise with the Vega, but ended up spending months campaigning against the repressive charges against the other Greenpeace members laid by the Queensland police. Eventually in October she left Brisbane to join a protest at Pine Gap, and from there proceeded to New Zealand. It is all part of the same struggle.

The trial of the Brisbane Seven is set for April 1988. The year 1988 is a significant one for the Queensland government, as Brisbane hosts the World Expo and thousands of overseas tourists. Opponents of the government's repressive social and political policies will be attempting to alert visitors that what appears to be a tropical paradise is, not far under the surface, an inhospitable climate for democratic dissent.